My baby was in the ICU.

My baby, who isn’t really a baby anymore, could have died. That’s not what I want to tell you about but I probably need to start there.

As of last Friday, my son had been suffering from what appeared to be a very severe migraine for three days. On the long list of his various diagnoses, migraine hasn’t historically appeared, so we’d decided he should come home. If it wasn’t better by Saturday morning, I’d take him to the ER.

Saturday morning, we drove to the local hospital. They ran a CT scan, an MRI to confirm, and then we found ourselves behind a curtain with a very concerned doctor telling us my son had extensive blood clots on his brain. Our local hospital, the doctor informed us, was unequipped to offer more than the most basic of interventions, so he would need to be airlifted to the big city research hospital two hours away.

Airlifted, for god’s sake.

He wasn’t airlifted, in the end. It was quicker to get him in an ambulance, alone. No family allowed. Meanwhile, we— his dad, his girlfriend, and I— all scattered to our various homes and cars to collect whatever we might need for an unspecified number of days away from home, promising to meet him at the new hospital as soon as possible.

My preparations included briefing his sister, holding them while they cried, and then leaving them, alone, to go to work and arrange overnight company for themselves. It felt like reaching into my chest, pulling out my heart, stuffing a corner into their trembling hand, and then sticking the majority back inside. The connection pulled thinner and thinner as I drove down the snowy highways towards their brother and I feared it would break. That my daughter would not be able to hold on and the tail of my absent heart would just be flailing, loose, in the winter wind.

In all the writing I’ve ever read about single motherhood, this reality is never mentioned: if you have more than one kid there will come a day when one of them will need every bit of yourself you can muster, you’ll have to desert the other one in some kind of way, and it will break your fucking heart.

While I slept on the origami couch in the corner of my son’s room in the ICU, his girlfriend slept on the recliner and his dad cycled in and out, two hours drive each way, over and over. The first night, the nurses woke him to do neuro checks every hour to make sure he wasn’t bleeding into his brain or heading towards a seizure. He had IVs everywhere— both arms, both hands— each with its own complex array of tubes, as well as heart monitor patches and some kind of lit-up cap over the end of his index finger, all attached to wires leading to monitors that beeped incessantly.

He couldn’t sleep. He couldn’t eat or drink. Any light pained him. So, we held vigil together in the dimness, our shallow breaths keeping time with the drip, drip, drip of the meds through the tubes, the beep, beep, beep of his erratic heart.

Here is the thing I want to tell you, though. Not what happened to my son, but what happened to me during those endless hours on what felt like another planet. Things inside me shifted unexpectedly. Stories upon which I’ve based my life heaved and settled into new configurations.

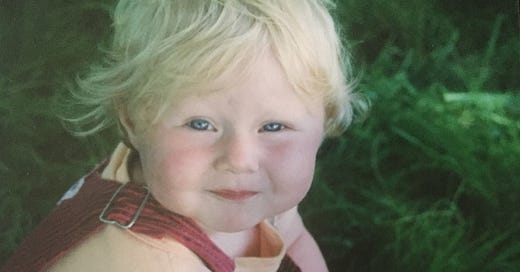

Maybe it’s true for any parent in crisis mode, but with my Single-Mama-Taking-Care-of-Business hat on there’s not a lot of room for feelings. Attentiveness verging on hypervigilance, yes. Competency veering into (maybe some teensy-weensy) control issues? Also, yes. But fear and panic get pushed way down, to be dealt with at some unknown, future time. So, I wasn’t consciously scared, or overwhelmed at the possibility he could be permanently disabled, or struck dumb that he could have died. Except for a few, brief moments in the car, racing towards the hospital, trapped behind someone driving under the speed limit on the twisting, two-lane highway. Then it just rolled over me. I might outlive my own son. I might have to bury my baby.

Mostly, though, I moved around like a disembodied head, both focused and floating. And somewhere amid that detachment, all of a sudden, it hit me in a way it never had before. When my brother— my abuser, the bogeyman of my entire life— died four years ago, my mother had to bury her son.

It’s not like I didn’t understand that, intellectually. But I couldn’t really get past my relief, my sense of being released, as if his hands finally fell from my neck, in the immediate aftermath of his death. Empathy for anyone awash in grief over him, even my mother, who I love, wasn’t a feeling I could grasp a hold of.

But there I was, my son wrapped in tubes and wires, hiding behind sunglasses in a dark room, limp and sick for unknown reasons, not knowing when, or if, he might die, and I could finally let it in. I could imagine what it was to not just wonder if my son might die from the illnesses that plagued him, but know that death was surely coming, any minute now, maybe before his next breath.

The feeling of the tail of your heart slipping through his fingers and flailing, forever untethered, in the winter wind.

In all the writing I’ve ever read about single motherhood, this reality is never mentioned: if you have more than one kid there will come a day when one of them will need every bit of yourself you can muster, you’ll have to desert the other one in some kind of way, and it will break your fucking heart.

And then there was my ex-husband. I’ll be blunt, I don’t like my ex-husband. He was shitty to me during our marriage and even shittier during, and after, our divorce. I’m sure, if you asked him, he’d say the same about me. He’d be wrong, but it’s a free country, y’know?

We’ve managed to co-parent over the last dozen years by keeping our communication in writing and to the absolute, bare minimum. When we attend the kids’ various functions, we sit as far away from each other as possible. We don’t chat or acknowledge each other at all. Many people will say this is not okay, but it’s okay by me. I don’t allow people who treat me like shit any more access to me than is required by law. Period.

My brother taught me that. Not on purpose, mind you, but to survive him.

The silent avoidance the wasband and I have settled into over the years wasn’t going to work while our son was in a severe medical crisis, though, so we just, without discussion, set it aside. We texted updates back and forth, on and off, all day. When he would return to the hospital after hours away I would run him through everything that had happened since we last communicated. He would listen carefully, ask questions, and say thank you. We discussed tag teaming coverage at the hospital and he encouraged me to take time away to rest in my own bed.

And when it was subtly clear that between the three of us— me, my son’s girlfriend, and my ex— his dad was my son’s third choice for company, he gave way with good grace. When he was there, he laid his hands on our son gently and spoke to him tenderly. Then he returned home to give our daughter as much presence and attention as possible. I was grateful for that, and I told him so.

He was a good dad. Just like my brother, in the last years of his life, was a good son.

I’ve written here before that I don’t really understand forgiveness. None of the Christian ideas of forgiveness I was raised on account for the reality of irreparable harm or the necessity of repair. Instead, they force victims to accept abuse over and over to prove their goodness while abusers act with impunity.

More secular ideas circulating now, suggesting forgiveness isn’t for them, it’s for you are hard to swallow when you’ve been actively gaslit for decades. When you’ve been told, over and over, it never happened. You’re being overly dramatic. If anyone has suffered, it is them. They are the victim, not you, you lying, crazy, awful bitch.

Holding tight to my anger, clutching the truth of what happened behind closed doors close to my chest, felt like the only way I wouldn’t disappear entirely.

But here’s what I know now, and you can call it forgiveness, I guess. Regardless, it’s the deepest truth about loving people in a complex, often painful, and confusing world that I’ve been able to figure out: Who someone is to you isn’t all of who they are. But who they are for other people doesn’t erase who they are, or were, to you, either.

You get to make decisions about your relationships with people based on who they are to you, and no one has any right to tell you differently. But if you can hold the sometimes contradictory, illogical, and heartbreaking reality of all they are, even as you create whatever boundaries you need to keep yourself safe and sane, it will bring you peace. You deserve peace.

If it takes a long time to get there, that’s alright. There aren’t timed trials. It’s not the Peace Olympics. But if, out of the blue one day, the story expands and shifts under your feet, affording you some unexpected acceptance and tranquility to stand in, let it. I’m with you, just allowing that shit like there’s no tomorrow.

My son is okay, by the way. Not great, but okay. He’s home now, safe and sleeping in his own bed, surrounded by his beloveds. We don’t know yet why his symptoms developed or what will happen in the future. But he’s responding well to treatment, has an excellent medical team, and, in the capitalist hellscape of our healthcare system, is lucky to have excellent insurance. Thanks be to his dad for that.

And thanks be to all the incredible healthcare professionals who cared for him so well and lovingly. It’s easy to forget right now with the current administration making everything so goddamned awful that there are, even as you read this, so many people working their asses off to take care of others. Not because those in need of care are worthy. Just because they’re human.

I hope when you need care, which we all will someday, they’ll take care of you. I hope that for everyone.

XO,

Asha

Dearest friend,

oh my maternal heart…your words hit home on many, many levels. we can talk more about when we go to buffalo together 💛 until then, holding you in love and wishing you and your strength and healing in recovery.

xoxoxo

This is beautiful, Asha. There were so many lines I'd highlight, but this part really hit home: "Who someone is to you isn’t all of who they are. But who they are for other people doesn’t erase who they are, or were, to you, either." I'm so glad your family is OK for now.