I spent most of the first 40 years of my life outside my body, and not just when I was having sex, though that was a habitual trigger to get the hell out of Dodge, so to speak. When I was in my body I got as far as my head, but below the neck was another country and I didn’t speak that language with any level of conversational fluency.

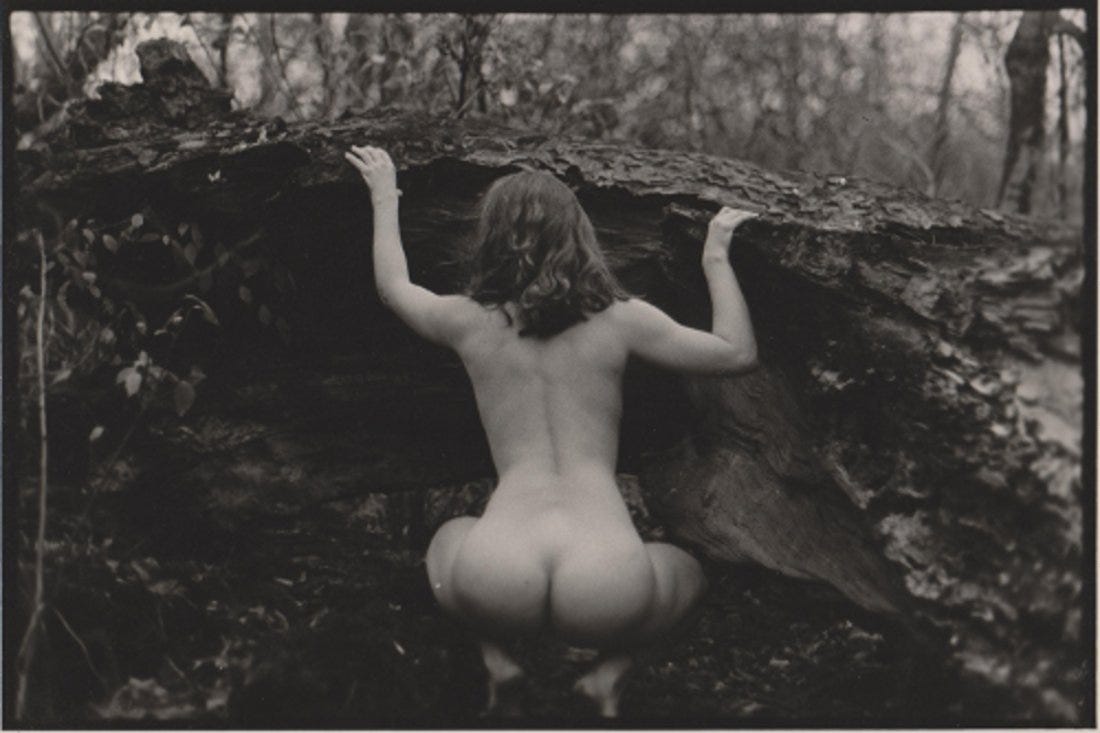

Just like with a language, in immersion situations, I could drop in and manage to get around passably well. In the woods as a kid, I could drop down and be entirely present for hours, and very occasionally for days at a time. But once I got back to the “real world” I was up and out again.

My disassociative tendencies were originally learned in response to childhood sexual trauma, but trauma was not the only factor that dug those grooves so deep in my psyche. We have this narrative in Western culture about the mind/body split. The mind and spirit, which are traditionally associated with the masculine, are ideal. The body, traditionally associated with the feminine, the wild, the animalistic, are base at best, sinful at worst.

Living in a finite body is often painful and bewildering, sometimes even terrifying. As a result, we have built religions and philosophies that work hard to transcend the body, elevate the mind, and denigrate anything and anyone considered “impure” or, more recently, “unenlightened”.

Women are allowed to be in their bodies as long as they are concerned with making themselves “attractive” in order to be appropriately objectified, which will then lead to them being reproductively useful to men. Men are allowed to be in their bodies in order to conquer, dominate, or seduce. No one is allowed to actually enjoy their bodies. No one is allowed to be disabled or fat or queer or trans or simply weird and wild and funky.

In rebellion against all of this personal and cultural disassociation training, I have been trying to climb back down inside my body for decades. Though I do still occasionally find myself ungrounded from what is happening, it’s rare (and deeply unsettling as opposed to unremarkable). How have I managed to do that?

Primarily, it’s been through a long, careful excavation of my emotional history and patterns. Some of that excavation has happened through talk therapy, but as much has happened through private study and conversation with my nearest and dearest. When I could afford it I’ve also used body-based practices, like massage and acupuncture. Moving outside as much as possible is, luckily, free.

Though I tend towards verbal and cerebral processing— thinking and talking about my emotions— which tend to encourage staying above the body, over the last ten years I’ve been steadily sinking down in. Now, when I feel a big emotion rising up I pay attention to what’s happening in and with my body. Do I feel it in my body? If I don’t, do I need to move my body (go for a walk, generally) to get down into what’s actually going on? Am I off-ramping in some way— overeating, craving a drink, or a cigarette? Can I stay in whatever I’m feeling and not run away, trusting that it will pass through and maybe lead me somewhere I need to go?

Committing to this long process of embodiment and emotional uncovering has helped me develop a certain degree of emotional intelligence. Emotional intelligence isn’t simply being able to put words to emotions, to bring the head to the heart. It’s actually becoming fluent in the language of the body and the way that emotions live in the body. It’s learning to pay attention to other people’s emotions and how they express them through their bodies and behavior, not just the words that come out of their mouths.

There are those who say that’s all there is to emotional intelligence— understanding the realm of emotions well enough to “read” yourself and others. That view allows for the use of emotional intelligence in pursuit of emotional manipulation, and you won’t be surprised to know I don’t believe we can leave it there. For me, emotional intelligence is grounded in a more caring and collective sense, a more feminine sense, and has an inherently ethical component. The emotionally intelligent person doesn’t subscribe to hierarchical evaluations of emotions or persons, any more than a lover of language might embrace notions that some words are “bad”.

Here’s what I wrote about emotional intelligence for my friend Rob Brezsny:

For me, emotional intelligence is personal, in that it connotes a person who has committed to understanding their own emotional history and tendencies in order to make more conscious choices about how to act, or not, out of their emotions. The emotionally intelligent person takes full responsibility, always, for their emotions and how the way they bring those emotions to the world impacts it.

Emotional intelligence is also relational, because it enables the individual to attend to patterns of emotional behavior in others and account for those emotions constructively in how they communicate and behave in response to what they sense, hopefully with an eye towards greater connection and deeper mutual respect and care.

Essential to this is a clear sense of "what is mine and what is yours." Folks who are emotionally intelligent can be empathic, but they work to be clear about what comes from them and what they are absorbing from others.

Finally, emotional intelligence is social. The emotionally intelligent person understands that institutions and systems encourage certain emotions and discourage others. These same institutions and systems often are based on power hierarchies, so they dictate who is "allowed" to feel what and when.

The emotionally intelligent person understands this and stands aside from it as much as possible, refusing to submit blindly to it or forcing others to submit blindly. The emotionally intelligent person wants everyone to own themselves, and not to be owned.

What does all of this have to do with integrity? Integrity is the practice through which we integrate our ideas and beliefs with our outer lives. Our emotions exist as the gateway between these two realms of experience. They filter what comes in and what goes out. And perhaps more importantly, how it goes out. The exact same words can be said with anger or contempt as with resolution or vulnerability, but the impact will be necessarily different.

All the grand ideas about people and how the world should be mean nothing if your emotional life is so stunted that you can’t actually connect with or see other people clearly as they are. Ideas and beliefs sequestered in the realm of the theoretical because you can’t translate them into real life and relationships aren’t worth very much.

When we ask ourselves, “How is this belief actually working for me? What world does it create for me? How is that world going to work for other people who aren’t me?” what we run into more often than not are the limits of our, and sometimes other people’s, emotional intelligence. Our integrity practice, the extent to which we can move through the world with our beliefs and our lives functioning as an integrated whole, interacting with others as if they are also whole people, is entirely dependent on our emotional intelligence. Is it easy to develop? Not particularly, in a culture that is so deeply disembodied. But there is no other way.

Are you emotionally intelligent? How did you develop that knowing?

This being the first newsletter out to my whole list since it was launched, I should let y’all know that Substack has launched an app for iPhone. You can find it in your app store. It’s free! An Android app is coming as well.

I am a bit of a curmudgeon, so I haven’t upgraded my iPhone in years. Therefore, I don’t have the necessary operating system and haven’t played around with it. But folks in the know say it’s a more streamlined experience. So, if you are the sort of person who prefers app notifications to emails and has a not-ancient iPhone, you can opt to read this newsletter in the app instead of getting it in your inbox. Enjoy!