I read an article in the New Yorker recently that posed the question of whether we are the same people as adults that we were as children. The author, Joshua Rothman, referenced books, essays, and documentary projects. He described research studies that tracked people periodically through their lives to see how their personalities and self-identifications remained stable (or not) as they grew. It was fascinating and prompted so many thoughts that I expect I’ll be returning to it here more than once.

In the end, Rothman suggests that whether we see ourselves as changing dramatically over the course of our lives or remaining the same person continually is less about empirical truth concerning the nature of humans and more about how the narratives we construct about ourselves function. If we see ourselves as changeable creatures then we may set ourselves up more readily to be that. If we see ourselves as constant, we may interact with the inevitable whirlwind of life that circulates around us as an exercise in consolidating our consistent selves. Our stories create us.

Looking back on my own life I think I exist somewhere in between those polarities. My faith calls me to a belief that there is an eternal aspect of who I am that never changes, a soul that came in with me and is always calling me back to my most essential self. Then there is my personality, which is wrapped up in my ego, and that has changed over time by necessity. So much of the personal work that I have done over the course of my life has been focused on this change, in fact. On tempering my destructive impulses, slowing down my reactivity, and developing my capacity for vulnerability and courage.

But there are also parts of my personality that were molded by trauma when I was so young I had no developmental capacity to withstand that manipulation, and those parts have largely not changed at all over the course of decades. They have resisted every healing modality I have tried to prod them into motion or transformation. They feel utterly and completely stuck.

When I first started going to therapy nearly 30 years ago the description of the human response to threat provided only two options— fight or flight. Looking back on my childhood and young adulthood I knew I hadn’t truly fought, but running away didn’t feel exactly true to my response either. It was only in more recent years that a third option was introduced to this schema— freeze. Yes! That expressed it exactly. This learned tendency I have in the face of stress, overwhelm, or any perceived (or actual) threat to internally curl up into a ball, breathe as little as possible, and just wait for it all to be over.

The image of the stuckness I feel that has come to me repeatedly in recent months is of my heart being shackled, encased in a knot that does not allow it to expand fully, to function optimally in the way it was designed. Presented with opportunities to love and create I feel like I can sense what my response should be, could be, but I can’t quite get to it. The knot creates inertia that holds me in place, as if I am still waiting after all these years for someone, anyone, to come and save me.

Talking and writing about it hasn’t loosened the knot. My abuser dying nearly two years ago didn’t release it either. It was, I realized, an issue of trauma trapped in my body, and I began to expect that something drastic would be required to dislodge it. So, I signed up to participate in an ayahuasca ceremony.

For those of you who don’t know, ayahuasca is a psychedelic plant medicine that has been used ritually to promote healing in indigenous communities in and around the Amazon jungle for thousands of years. A Peruvian shaman happens to live part of the year here, outside of Ithaca, with his wife, and they conduct ceremonies in a yurt at their off-grid compound. Close friends have done it and I wouldn’t even have to travel. If it was only one night, with people I trusted, and I could be home afterward in less than a half hour, how bad could it be?

In order to attend, participants have to set an intention and meditate repeatedly on it in the weeks leading up to the ceremony. My intention was focused on that inextricable knot caused by childhood trauma. I asked Grandmother, as the spirit of the plant medicine is called, to release that knot, to show me what love is possible beyond it, so that, ultimately, I could offer up some love to my abuser, my brother David.

Why bother to ask for love for my dead abuser? It’s true, my negative feelings toward David are valid and well-deserved. I wasn’t asking for them to go away completely. But I also know, intellectually, that he wasn’t just who he was to me. He died held by people who loved him. Even though he is far past caring what I feel (and I’m not sure he ever did), to be able to also offer some kind of love to him felt like it would be the truest indication that the trauma wasn’t trapped in my body anymore.

It was a tall order, I know. To undo a lifetime of trauma response in a single night. But I had read enough about other people’s experiences with ayahuasca to be hopeful. If I weren’t able to find hope even when it seems least available I would have given up long ago.

In the end, it was too much to ask of a single night’s labor. And labor is exactly what it was. The only initiations I can compare it to are my two homebirths, which cleaved me wide open and showed me what I could withstand. The experience was deeply uncomfortable, decidedly unpleasant— the sweats, the disorientation, and so much purging. Who knew you could vomit so much with only water in your system?

It felt like in response to my request Grandmother replied, “No skipping steps. If you want to release the knot then you have to feel what the knot is made of.” Then she left me for hours awash in fear and grief.

Once the medicine kicked in, the shaman, medicine, songs, and tobacco smoke all became extensions of David. Not like I hallucinated he was there, but more like he was haunting me through them, and I had to finally fight with everything I had. I lay there, shaking my head, beating my hand on the floor as if begging for mercy, and muttering emphatically, “No. I don’t want this. Don’t make me do this again. I don’t like this. I don’t choose this. You suck. Go away! No!” Intermittently, I would sit up, purge violently, and then collapse into my prone resistance again. Then, for a long time, I crouched on my knees, head on the floor, tears streaming down my face, and simply cried, “Why?!?” over and over and over again.

I came out of the medicine with the feeling that I had only glimpsed the tip of the iceberg in terms of the work to be done. But I had felt the feelings, descended into the depths of them, and wasn’t annihilated by them. If I can feel the feelings then they are moving, not frozen. If they’re moving then eventually I can move beyond them.

I did not receive a vision of love beyond that knot, didn’t reach some feeling of filial love for my brother like I had hoped. But for the first time, I can say this: I do not think my brother was born a monster. I think an avalanche of traumas buried him steadily, starting when he was only a baby. When he turned to drugs and alcohol at a young age, undoubtedly to self-medicate the pain of those traumas, he succeeded only in excising his capacity to constructively confront his pain, his choices, and his effect on other people. The world made him a monster, and he made himself an accomplice.

Even though I feel no love for him as my brother, I ache for him as a fellow human being. He walked a horrible path that I would not wish on anyone. Perhaps carrying that in my heart is enough.

Will I do another ceremony? Use that medicine vehicle to further transform the trauma responses I carry in my body? Maybe, but not soon. It feels like there is still plenty to process from this experience. To rush into another ceremony would be, as Grandmother said, skipping steps. I don’t think I should do that. I don’t think that would serve my story.

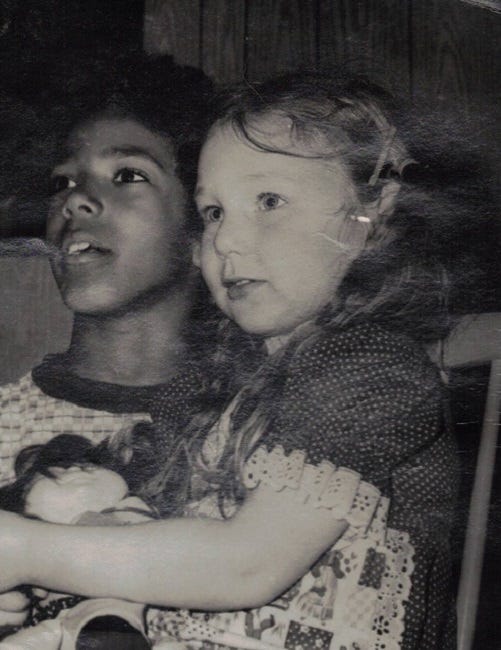

Walking each step, slowly but surely, feels like the right thing to do. It allows me to enact the change necessary to free that girl I was before it all began, to let her grow up, live a full, vibrant life, and tell her complicated story.

My heart feels tired, but more malleable than before. How is your heart today, friends?

I want to use this space to acknowledge and honor the compassion you have in your heart for David. Thank you for writing so clearly about the complexity of holding compassion for one’s abuser while at the same time never diminishing the impact of the harm the abuser does, or excusing it. I have some inkling of this, although my own experience of sexual abuse is quite different than yours. I remember that when the man who raped me was found guilty by the jury, I cried. I wept for two reasons: 1) I was so thankful and relieved that the jury did not let this man go free; and 2) I was heartbroken and sick that he was being sentenced to prison, an ugly and frightening place that is used not to rehabilitate but to punish and vilify people while at the same time reifying structural racism. I was shocked that I felt these two things at the same time and did not have the words to articulate these feelings. I was also afraid that no one would understand me if I tried. So again, thank you for showing how both can exist at the same time. ❤️

Your vulnerability and openness leaves me in awe. Having suffered abuse and resulting, lasting trauma, I continue my own healing path. It comes in fits and starts in its own time, and has been relatively gentle. In my own experience it cannot be forced. Big hugs and love to you as you seek.