We've got it so good

Will we understand before it's too late?

It’s easy to be cynical and assume the chronic myopia that characterizes many these days is solely an American problem. But not appreciating how good you’ve got it because all your life it’s just been this way is a human problem.

The second time I went to Cuba, the year I turned 25, I was there for about six weeks. I spent most of them living with a Cuban friend in his apartment, riding a rickety, no-gear Chinese bicycle across town every morning to study Spanish intensively at the University of Havana.

Being there long enough to get semi-embedded in the community allowed me to make more friends, including a group of young artists who liked nothing more than to shamble up and down the Malecón— Old Town Havana on one side and the sea on the other— talking and drinking, seeing and being seen.

It was on one of these promenades that we had a conversation I will never forget. All of these young people had grown up post-Revolution, and say what you will about the authoritarian tendencies of the Revolutionary government (which I would not deny), they had benefitted from many of its social policies. They were all highly educated regardless of their race or social status. They had all had access to high quality, cheap healthcare from the moment they were born. They were all housed, with no fear of ever being otherwise.

I described the realities of homelessness in the United States, the tens of thousands living on the street all across the country. They looked at me as if I had sprouted two heads. Then I recounted how much a standard, four-year, university education cost American students, and how many spent the vast majority of their adulthood buried in debt as a result. Their mouths fell open, jaws hitting the pavement, and then they admitted, “We’ve heard all of these stories before on state television, but we assumed they were just propaganda to keep us from immigrating. That with all the resources the United States has, they couldn’t possibly do that to their own people.”

I didn’t tell them not to immigrate. I admitted that the U.S., if they could make it here, might end up being a better fit for their artistic temperaments (Artists are often, at heart, strongly individualistic, a poor fit for the collectivism of a system like Cuba’s.) But I also told them they had no idea how good they had it in many respects. How could they?

I believed it was worth understanding what they would be giving up and that they would simply be trading one complex, imperfect system for another. I still believe that.

I found myself thinking of those conversations this week on the heels of reports that the State of Florida is moving to eliminate all vaccine mandates for its citizens, including those required for students attending public school. Do the people making decisions in Florida, or any of the people cheering on their decisions, truly not understand how good they have it? Did they not grow up knowing someone who suffered one of the diseases that has been eliminated (or nearly so) by modern vaccines? Because I did.

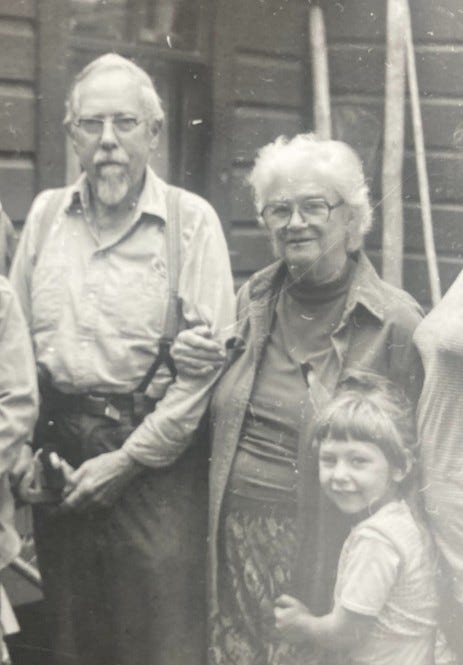

When I was very little, my family periodically extended to include an elderly couple in our Quaker Meeting, Dorothy and Egbert Walker. The Walkers owned an off-grid, family cabin on the coast of Northern Maine. They were willing to share their cabin with us for free— a huge boon since we had no money otherwise for vacations that didn’t involve visiting family— as long as we took them with us when we went.

Over the years, as their own family expanded to include kids and, eventually, grandkids, they had built themselves a shelter down the hill from the main cabin, just above the top of the rock line, which allowed them to have some privacy. Some of my favorite nights were those I got to spend down in the Bear’s Den, as they called it, with Dorothy and Egbert, nestled deep under the covers (because even in the summer, nights in northern, Coastal Maine can be very cold), then waking to the sun rising over the Atlantic. The smell of the coffee brewing in the pot on top of the potbelly woodstove and the fiery sun peeking over the horizon at me, my nose still cold in the frigid air, was a holiday feast of sensation.

My other favorite times were when Egbert would take me wild blueberry picking. We’d walk slowly down the driveway and across the dirt road to the other side of the peninsula where the blueberry bushes grew in profusion. Egbert would scope out a good spot and then I would help him ease down to sitting. He’d methodically pick every berry he could reach all the way around himself while I ran around like Sal in the classic children’s book by Robert McClosky about life in Maine, Blueberries for Sal, a dozen blueberries shoved in my mouth for every three that made it into my small, metal pail. Kerplink! Kerplank! Kerplunk!

The walk to the blueberry patch, the walk down the path soft with pine needles to the Bear’s Den, and every walk with Egbert was slow and deliberate because Egbert walked with a cane. Egbert walked with a cane because he was palsied on one side from the polio he’d suffered as a child. His back when he walked listed like a ship in a storm, his one arm pulled in tight to his side, and his hand, held against his chest reflexively, was perpetually clawed. He limped like one leg was slightly shorter than the other, though it was more likely that the muscles of his leg on that one side were withered and shrunken, just like those in his arm.

Egbert’s palsy meant he couldn’t drive, so all the years of their life together, Dorothy was the family driver. By the time I was small, making the drive from Washington, D.C. to northern Maine alone was too much for her. This was why they struck the deal with my parents, functioning as surrogate grandparents in exchange for getting a ride north each summer.

So, maybe I should be thankful for Egbert’s polio? Otherwise, he and Dorothy might never have needed us to get them to Maine. I might never have slept in the Bear’s Den or gone wild blueberry picking. I might have missed his botany lessons, when he would smear a blueberry on a slide and focus the microscope on the counter in the back room, holding the chair steady so I could climb up and peer inside. Who knew, like all fruits, they really did have seeds? I might have missed listening to my father roar with laughter over Egbert’s definition of a pessimist: “A man who always wears a belt and suspenders.”

Egbert’s life was deeply rich far beyond his relationship with us. He and Dorothy were happily married for decades. They raised children and delighted in their grandchildren. They were active members of our religious community, and Egbert was an accomplished academic, traveling and teaching about his specialty— the botany of Japan.

Disability, either physical or mental, is never an inevitable impediment to a rich and satisfying life, which Egbert undeniably had. But would he have preferred a life free from chronic pain and physical limitations? Was he grateful his own grandchildren never needed to fear contracting polio like he had once the vaccine was widely distributed in the United States? I have to assume so.

Instead, now his grandchildren’s peers are setting up an entire state to suffer like Egbert did. Because they will suffer. Be it polio or measles, tetanus or diphtheria, preventable illnesses will infect people, permanently disabling or killing many, all because a whole host of people refuse to understand how good they have it. Or don’t believe in science. Or don’t actually care how our choices, for ourselves and our children, aren’t just for us. They’re also for our community— our grandparents, neighbors, and friends. For people we might never meet, but who are still connected to and affected by us.

I’m not totally lacking in sympathy for those parents who are skeptical of the pharmaceutical industry or hesitant in the face of all the vaccine misinformation circulating out there. A lot of that misinformation was out there when my kids were babies, adding to the actual lack of information about auto-immune disease, which my kids had coming down on both sides of the family. I felt overwhelmed at the enormity of my responsibility to protect them, and I didn’t trust that people in authority knew or cared enough to help me.

So, I chose to delay vaccinating them until after their first birthdays because I’d heard repeatedly that the human immune system until then isn’t fully developed and is prone, given genetic tendencies, to shift into overdrive when overstimulated by vaccines. Is this true? I still have no idea. Also, to be honest, the delay didn’t work to prevent my children’s suffering. Both my kids have auto-immune diseases— just like me, their father, and any number of extended family.

Could I have prevented that suffering by never vaccinating them? Probably not. But even if I had, they would have suffered in other ways. Preventing all our children’s suffering is impossible, and we potentially create as much suffering by trying.

I did get them all caught up on their vaccines before they started public school. It felt like a reasonable compromise between my protectiveness and my obligation to my community. Would I do it all the same way again now? Honestly, I don’t know. I wasn’t even on the internet when my kids were babies. Now, I could do better research, which might balance out my inbred mistrust of authority and Western Medicine. But it’s also possible the sheer volume of misinformation out there might overwhelm me even further, playing on my primal fear.

In the end, I believe we were lucky. That neither of my children contracted or passed along a serious, debilitating, preventable disease before I got them vaccinated. That my compromises, at the very least, protected our community. Would Egbert be proud? Or having been disabled nearly all of his long life due to a disease I was able to prevent my children and anyone in my community from getting, would he explain the science like the teacher he was and then tell me to get over myself?

I can only hope I would listen, just like my Cuban friends listened to me all those years later. I certainly owe Egbert that. I think we all do.

Your story about your Cuban friends reminds me of when my friend from France was living in my basement on a long vacation here, and his bandmate came to visit us--a rock n roll guy who considered himself too cool for politics. My other roommate got a random infection in her toe, and came home from the urgent care with a $400 bill to lance it and get some antibiotics (this was almost 20 years ago, I imagine it would be much more now), and he was so horrified at what she had to pay to get basic care for something so silly. "Why are you all not rioting in the streets?!" he demanded to know. I think about that all the time. Indeed, why are we not all rioting in the streets?

I also really appreciate how much grace you give to the full spectrum here. My family are all anti-vax (and live in Florida, surprise, surprise), and I know that as much as I am furious with them, I know that their fears have been exploited and it's not easy to sift through scientific information as lay people. Whew. Thank you.

I'm usually averse to Facebook, but this is one that I had to share to my "public". Thank you, Asha!!