Any of you who’ve been reading the newsletter for more than a minute know I grew up as a Quaker. For Quakers, integrity is a central religious imperative, or testimony, as we call it. I set out to write this newsletter largely because I wanted to open up the conversation about integrity that I grew up steeped in to a broader, not necessarily religious, audience.

Increasingly in the United States many of us aren’t religiously affiliated at all. And yet we still want to live deeply grounded, meaningful, moral lives. So, how do we learn how to do that? Where do we have the necessary conversations? I hope some of the how and where is found here, in this newsletter.

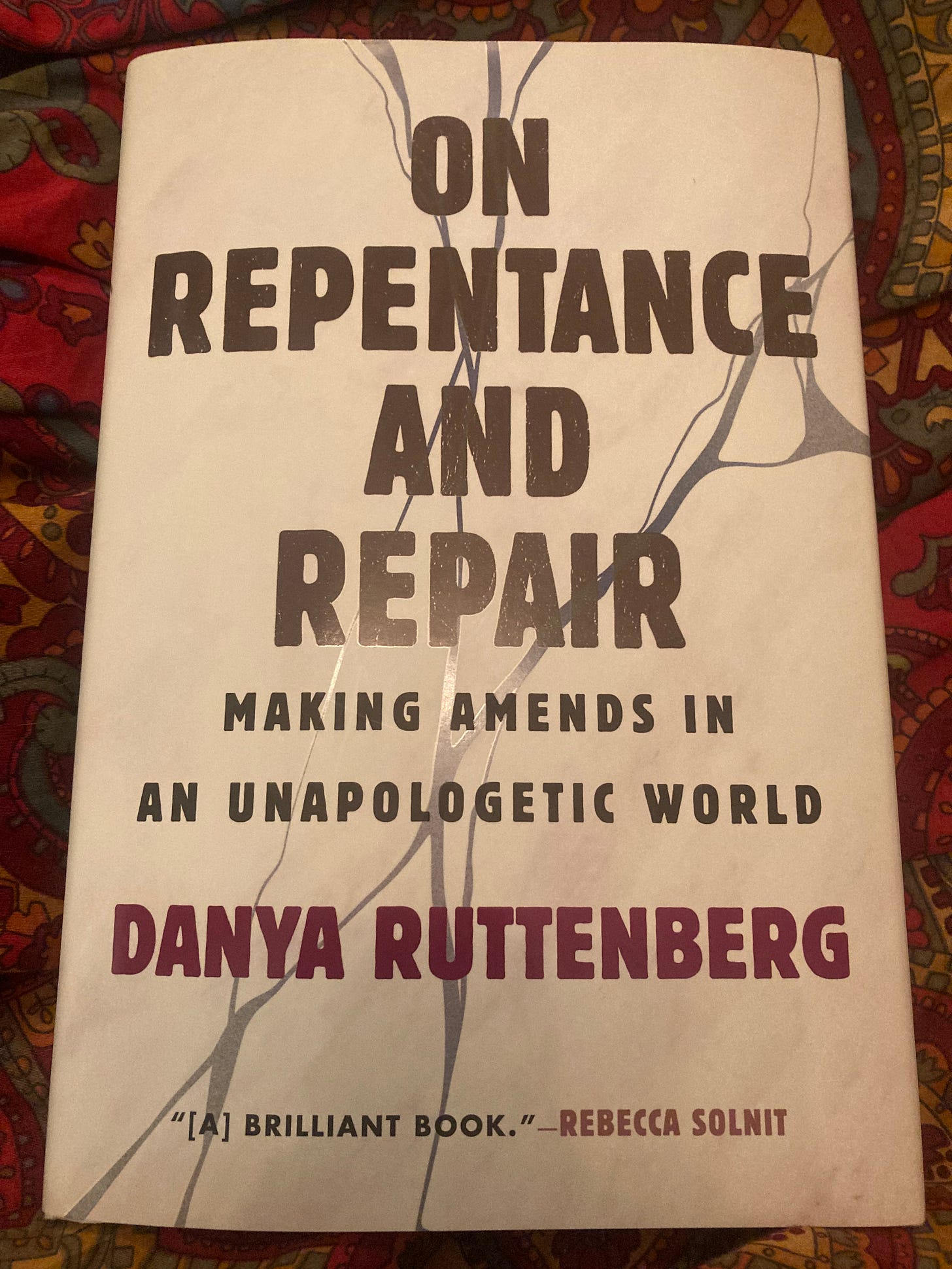

Another place to learn how is in a book I recently fell completely in love with, On Repentance and Repair: Making Amends in An Unapologetic World by Danya Ruttenberg. I first heard Ruttenberg interviewed about her book on the We Can Do Hard Things podcast. Then, I searched all over for a copy of the book, which was on backorder nearly everywhere. Finally, I found a single copy, and when I was partway through I scrounged up more copies and had them sent to two of my dearest friends and my mom. In the process, I also discovered Ruttenberg has a Substack newsletter, Life is a Sacred Text, which I subscribed to immediately. This is how much I loved this book.

In this book that I love, Ruttenberg, a rabbi, elucidates some of the central teachings of Judaism, namely the Laws of Repentance as written by 12th-century Jewish philosopher Maimonides. She explains the crucial differences, based on Maimonides, between repentance, forgiveness, and atonement, and lays out the five concrete steps of true repentance. She then applies those steps to a wide variety of arenas where we commit harm to each other— in families, intimate partnerships, communities, institutions, and nations— to show how they work, and where the most common pitfalls are.

Ruttenberg insists that despite Mainmonides having written exclusively for Jews trying to live within the confines of Jewish law, his ideas offer a useful framework for everybody. Because everybody experiences harm in a variety of ways:

I am, very intentionally, applying these concepts to secular life and relationships. It’s for Jews and non-Jews; for atheists, agnostics, and theists; for secular people, spiritual people, religious people, and for everybody in between. We’ve all caused harm, we’ve all been harmed, we’ve all witnessed harm. We are all always growing in our messy, imperfect attempts to do right, to clean up, to repair, to make sense of what’s happened, and to figure out where to go from here.

If you read that quote and thought, Wow, she sounds like Asha! Thank you very much. I do think this project and hers are kindred endeavors.

So, I love this book because we have similar underlying premises— to share the teachings of our faiths more broadly and apply them more secularly. But I also love this book because, honestly, Quakers really suck at repentance. Ruttenberg provided me with language about accountability I never heard growing up, and a concrete system that I could have used so many times in my life. I knew there had to be a more constructive way to deal with harm than I’d been taught, and Ruttenberg showed it to me. Finally!

My mom has said that most modern Quakers’ idea of pacifism is really just conflict avoidance. She’s not wrong. Unfortunately, you can’t engage meaningfully with the inherently confronting process of repentance, which involves naming and owning harm, offering apologies, accepting consequences, and seeking transformation, if you’re conflict-avoidant.

As a result of this conflict avoidance, Quakers tend to skip over the discomfort of honestly working on repentance, instead jumping straight to forgiveness and reconciliation. Unfortunately, forgiveness without repentance is what theologian Dietrich Bonhoeffer called “cheap grace.” In pursuit of quick and comfortable closure (for those not directly harmed), we can also lean hard on victims to bear the burden of our discomfort, asking them to “let it go”, “move on”, and “forgive”, whether or not any amends or reparations are ever offered. Since they aren’t expected or (heaven forbid) required, usually they’re not.

Quakers aren’t alone in this tendency, as Ruttenberg clearly explains. In fact, our entire culture in the United States tends to eschew the hard work of repentance and accountability in favor of focusing on forgiveness. Individualism is one of the reasons. Protestantism is another, and capitalism is another still. A history of white supremacy and civil war is also central to our national repentance-avoidant temperament. Just like in the days immediately following January 6th, when Republicans leaned on everyone to skip accountability for Donald Trump and his cronies in favor of “national unity”, many Northern, White Protestant church leaders after the Civil War encouraged everyone to forgive the Confederates (and ignore the atrocities being committed against newly freed slaves in the South) in pursuit of a united American nationalism.

In that particular case, focusing on forgiveness and reconciliation while neglecting the work of repentance cemented existing power structures. Often when the work of repentance is avoided in families, institutions, and countries, maintaining the status quo, with all of its inherent injustices, is the implicit goal. And yet, Ruttenberg reminds us that not all harm is inflicted by those with greater power against those with less. To suggest that harm always involves power imbalances, in fact, would “deny something of our essential humanity”, she writes, “the way we all, as messy people trying to do our best, can hurt one another.”

It is worth mentioning that Ruttenberg spends relatively little time in the book on forgiveness and insists repeatedly that repentance and forgiveness are not dependent on each other. A perpetrator of harm can, and must, do the work of repentance whether or not they ever receive forgiveness. Forgiveness, if it is offered, is ultimately for the benefit of the victim. It should never be mandated, and it also may never lead to reconciliation. Reconciliation, again, being its own separate, albeit related, thing. Also, with some kinds of harm, even if the victim finds forgiveness for the perpetrator, the slate can never be wiped entirely clean. You can’t unbreak the egg. You can only figure out what to make with what’s left after it’s broken.

Ruttenberg mentions integrity often in her text, which makes sense. Integrity is relational. It’s about the moral quality of our choices as we bump up against each other in the process of becoming ourselves. Our ability to honestly confront the harm we inflict, suffer, and witness as we stumble along is essential to being a positive moral agent in the world. In other words, you can’t practice integrity without engaging with the process of repentance. You just can’t.

If you, like me, wrestle with what to do with the unavoidable harm in this messy human life, this book can help you begin to figure it out. I have to believe that we’d all be better off if we understood how to love each other better, and if we knew what to do when we don’t love each other well. What do you think?

If you want to buy Ruttenberg’s book, or any other book I’ve ever mentioned here in the newsletter, you can find them all in my online bookstore, provided via bookshop.org. To be clear, this is an affiliate link, so a small percentage of every sale will come to me. Another portion will go to the independent bookstore of your choice because Bookshop is awesome.

This week, but before…

One year ago:

Two years ago:

this makes me think of making amends as covered in the 12 steps. Repentance and atonement, regardless of forgiveness. Very interesting thoughts here. I don't have time to read the book, but I appreciate your review.

Maimondes is one of the most underrated moralists the West ever produced. He wrote the book "Guide for the Perplexed", that's basically a Cliff Notes version of the Talmud. Where the Talmud didactically lists (then) influential Jewish Rabbi's thoughts and musings in topics of law and morality in exhaustive and boring detail, Maimondes cherry-picked that actually important topics and boiled the Talmudic arguments down to 3-4 question rubrics. 3 questions to ask yourself when considering repeating a rumor; 3 questions to ask yourself when considering donating to charity; questions to ask yourself when thinking about forgiving someone, seeking repentance, etc. Can't wait to read Ruttenberg's book. Great article, glad I subscribed!