Welcome, welcome! I’m so glad you’re here! Since you went to the trouble to stop by, let me know you came? I’m historically a “leave no trace” kind of traveler, but let’s dispense with that ethic on this journey together, shall we? Hit the heart, leave a comment, share widely. Please, and thank you. XO, Asha

Is there such a thing as too much conviction? When does holding firmly to belief become grasping it like you’re drowning?

Learning to be a lifeguard, they tell you that people who are drowning can drown you unintentionally when you try to save them just trying to save themselves. Belief can often feel like something solid to hold onto in a chaotic tumble of a world that otherwise might pull us under. But doesn’t that make it, if not inherently dangerous, then at least danger-adjacent? Like at any moment, we might grasp our beliefs too tightly and inadvertently pull other people under in the process of trying to save ourselves?

The trouble, of course, the irony, is that we can’t practice integrity without conviction. Without deeply held beliefs, we have no scale to weigh and discern. Without principles, we lack standards, boundaries, and enough sense of how things should or could be to give us direction and purpose. People who are unprincipled are, by definition, wishy-washy, inconsistent, unreliable, and untrustworthy.

But conviction alone isn’t the defining characteristic of integrity, either. Conviction created slavery, burned women at the stake for witchcraft, imprisoned Native American children in Indian Schools, and fueled the Holocaust. Conviction has always been the impetus for atrocity. Otherwise, how would we justify ourselves?

Conviction only leads to integrity when it’s mindful of relationship and interconnection. It’s a social technology, after all, the mechanics of how we bump up against each other as we try to live our beliefs out into a world full of other people. People— not objects for us to act upon, or lesser creatures to control or dispose of at will, but people. Just like me. Just like you.

So, how do we find that balance? How do we feel and believe deeply without inflicting our beliefs on other people?

Thinking about the perils of conviction on a social scale is too abstract to adequately answer such questions, however. It’s easy to simply assume that we, of course, would not find the balance of conviction and connection troublesome when confronted with the sorts of horrors people, en masse, can inflict on one another. And, who knows? Maybe we wouldn’t, though I will admit to some humbling skepticism.

Better to contemplate the need for that balance on a more personal level, and what is more personal than heartbreak and betrayal?

I remember, in the midst of my own divorce, a former friend telling me that I should cut my ex-husband some slack when he was vicious or selfish or resistant to any degree of personal responsibility. Who is their best self in a divorce? she opined. And she wasn’t wrong about how challenging it is to balance conviction and connection when disconnection is actually the point of it all, but also… isn’t crisis when we’re supposed to really dig deep to practice our integrity? It’s not like we only trot it out when everything is going swimmingly and otherwise make excuses about how hard it is. We still have to at least try. The possibility of grace isn’t a get out of jail free card.

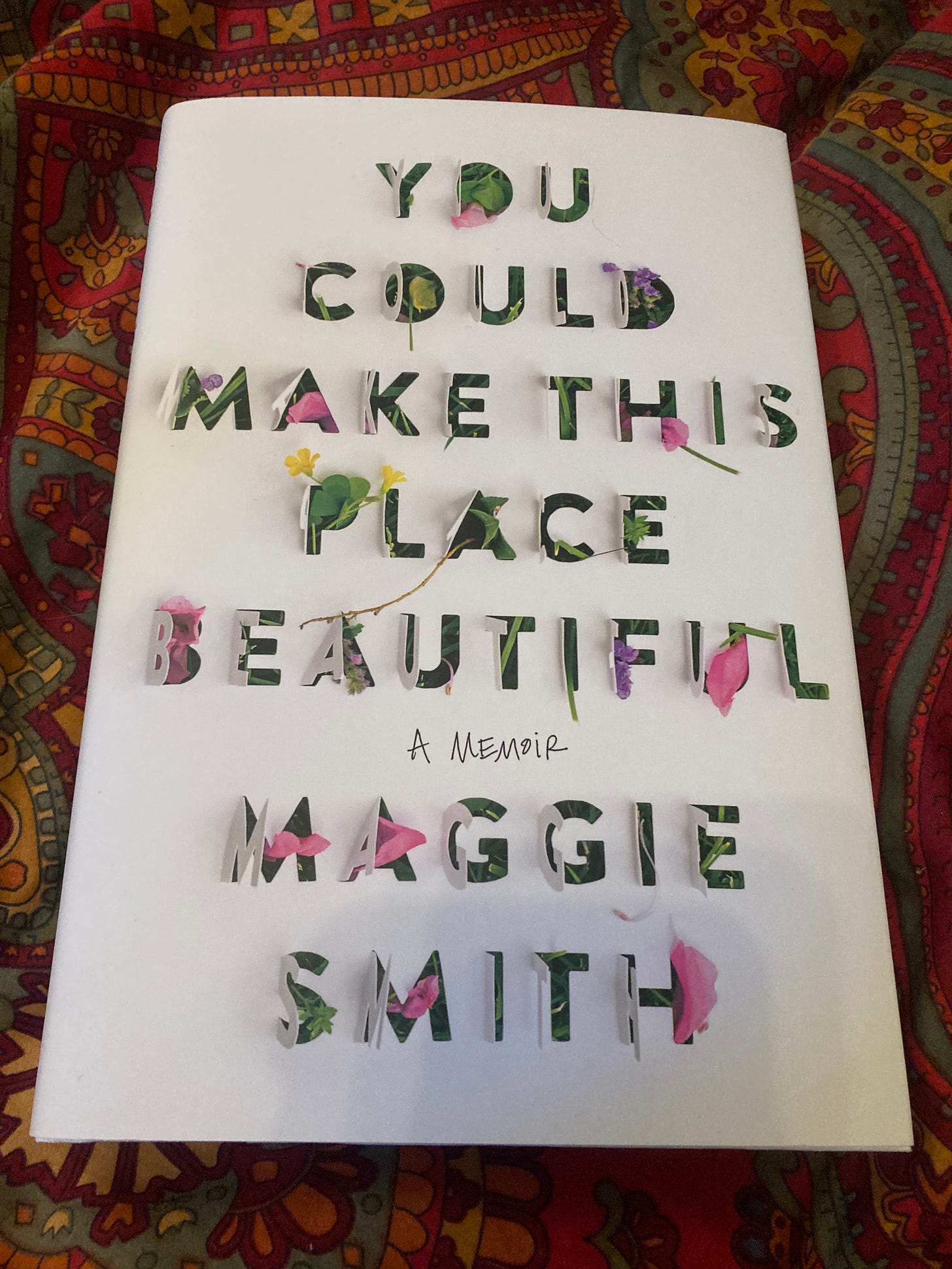

A couple of weeks back, I mentioned the poet Maggie Smith. You Could Make This Place Beautiful, her recently released memoir, which I’ve been losing sleep nightly reading, is a masterclass on this complicated balancing act. Spinning out the story of her own marriage and divorce she takes us on a journey that is painful and heartfelt. In the aftermath, she is trying to find herself again. Trying to understand how she lost herself in the first place to the gendered dynamics of power and priority so often found in heterosexual marriages, being that she is obviously a woman of strong conviction.

I love this description of herself that she offers, which illuminates the challenge of being exceedingly earnest and deeply emotional:

The Wife— The Mother, The Finder— would love to be someone who doesn’t give a fuck, or who at least give considerably fewer fucks, but she is not that person. That’s not how she was built. The Wife’s factory setting is GAF. She gives so many fucks. All the fucks.

Did I recognize myself in this? Do you? I suspect we wouldn’t all be here together if we didn’t. We are people who care, deeply, about all sorts of things, which is beautiful and perilous at the same time. Set on GAF, what wouldn’t we do to defend our people? Seriously, think about it. Is there a limit to what you would do?

From the beginning, Smith is clear that the narrative she’s offering is her version of the story, and a curated one at that. She’s honest about what she’s leaving out and why— certain information about her children, for instance, her husband’s name and that of his mistress, and details about the new love she eventually found for herself. But she doesn’t let the acknowledgment of the inevitable partiality of her story lessen the importance of it, or her hope that it will be of use. She writes in the prologue:

This isn’t a tell-all because “all” is something we can’t access. We don’t get “all.” “Some,” yes. “Most” if we’re lucky. “All,” no. There’s no such thing as a tell-all, only a tell-some— a tell-most, maybe. This is a tell-mine, and the mine keeps changing, because I keep changing. The mine is slippery like that.

Following along the winding path of her journey with her, I can’t help but think that it is exactly that consciousness about the slipperiness of self that allows her to find the balance of her integrity so masterfully. Even as she is clear about what she believes and feels, she is less clear about who she is, or is becoming.

Divorce is like that, in my experience. You lose who you were, as well as who you thought you would become. But in that unknowing, that threshold place between who you were and whoever you might become, you have the opportunity to remember that your beliefs aren’t ever who you are. Beliefs are something you hold, which means you can decide how tightly you clutch them. You can find that firm, light grip that allows you to act responsively and gracefully, to absorb the force that comes at you and redirect it where you want it to go without lethal damage.

In other words, you don’t let the tumult kill you, and you don’t kill anybody else either. Literally or metaphorically.

It is worth noting another aspect of Smith’s successful balancing act. For all of her curation of the story, she doesn’t shy away from her grief or anger. She also writes honestly about how betrayal makes for a neater story, a cleaner assignment of villain and victim, which is not necessarily true. Truth, like life, is more complicated than that. Letting herself off the hook is not what she’s after, which allows us to get hooked as well, to ponder the ways we are implicated in the crises of our own lives, no matter how obvious who’s to blame may be on the surface.

The book opens with this quote from Emily Dickinson: “I’m out with lanterns, looking for myself.” Smith searches through her history, relationships, beliefs, dreams, and desires. She is not looking to discern what is Right with a capital R, but what is true. What life she can construct for herself and her children that is authentic and loving and full— that doesn’t feel like a half-life, a life she was left with, but a life that is beautiful and right for her. Even in the midst of unknowing. Even while still juggling a contentious co-parenting relationship. Even without yet finding forgiveness, she is able to construct a life in alignment with her convictions and her heart that leaves space for everyone.

She writes towards the very end:

I’ve wanted for years to understand what happened, and part of me feels I’ve failed because I don’t fully understand— can’t fully understand because I don’t have access to the whole picture. I only have access to the mine.

What now? I am out with lanterns, looking for myself. But here’s the thing about carrying light with you: No matter where you go, and no matter what you find— or don’t find— you change the darkness just by entering it. You clear a path through it.

This flickering? It’s mine. This path is mine.

this book is a masterpiece, one that I'm writing and reading and finding myself too...because I also gave too many fucks. Way, way, way too many fucks.

I found Maggie Smith through my Christian Century newsletter. I'm so glad to meet her for the second time in your Friday posts two weeks in a row. You make her someone I'd like to sit with over a cup of coffee and share. Perhaps you could join us and she'd a little of your light as well. Asante sana! J.Confer